It’s no secret that I have a thing for geometric forms in knitting (see Cerys Hexagon Blanket pattern), but it might the inspiration often comes from surprising places. In the case of my new shawl pattern, Crystalline, it was a stroll down London’s famous Oxford Street one evening after work, and noticing this extraordinary three-dimensional glass facade above a very ordinary branch of Boots. You can see it for yourself on Street View.

Another source of inspiration was a visit to the incredible Teufelsberg on the outskirts of Berlin, a cold war listening post complete with geodesic radomes.

[If you are ever in Berlin, get yourself on a tour of the place before it crumbles, it’s quite an experience]

So how does a spark of an idea become a knitting pattern? My design process is probably a little different to most people, and I tend to go through a lot of iteration. I normally start with the knitted fabric, then document on paper afterwards.

My first iteration was the orange swatch from the collection below, a skewed motif inspired by viewing the Oxford Street building from an angle.

It was, well, a challenge. I couldn’t get the yarn overs to look good worked on both sides, or get sides to remain perpendicular to the edge (which could in itself be a desirable design feature, but I was already managing too many variables).

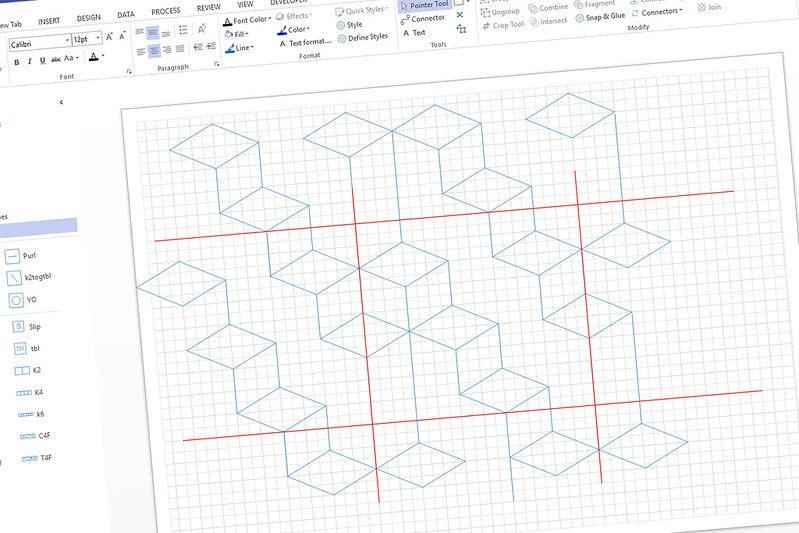

Next I moved to a motif based on three-dimensional blocks (which, in two dimension, are hexagonal shapes), and fired up my favourite drawing software, Visio, to sketch an abstract pattern repeat.

In some ways knitting is more suited to fluid, organic forms, than to rigid geometry, but hexagons do work well, thanks to the ratio of stitches to rows in stocking stitch being very close to that needed to make equilateral triangles, the building blocks of hexagons.

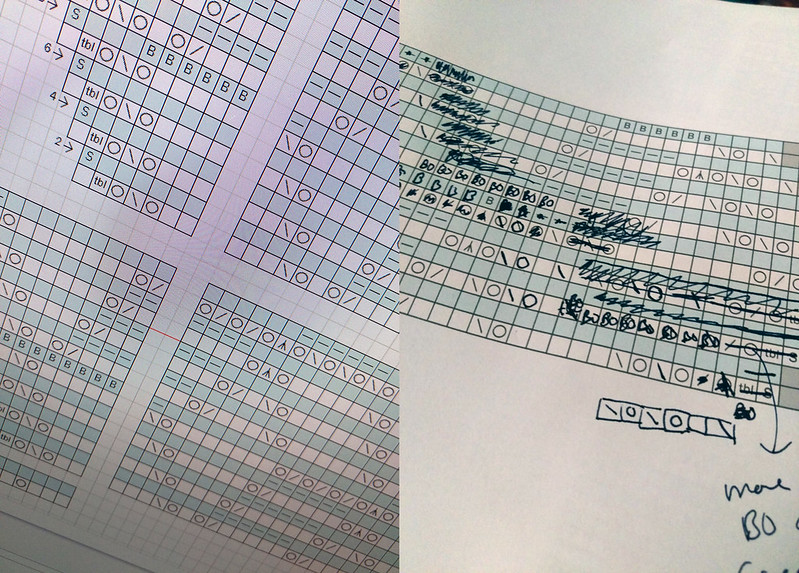

Another swatch and I realised that the stitch repeat was unfortunately too big to chart, so I simplified it again to a (relatively) simple block repeat. It took a few more swatches (shown above) to explore different methods of beading, decorative side edging and develop the staggered cast on. Finally it was time to get charting, yee haw!

But I was foiled by this complex design! The pattern repeat was actually too big to fit on an A4 sheet at a readable size, so realistically, no poor knitter would ever be able to knit this garment. I had no choice but to reduce the size of the pattern repeat, re-chart, and swatch again to check the shapes were still proportionally correct. Luckily they were, phew!

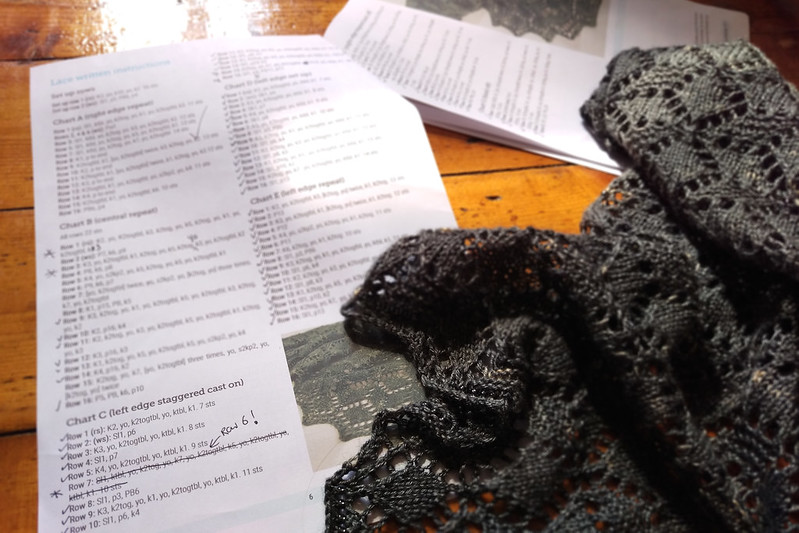

Then it was sample knitting time. Many designers don’t knit their own samples, but I find it to be an important part of the process. Not only does it give me the chance to iron mistakes early, but I get to have the experience of knitting the complete garment and I’m better equipped to help customers when they get stuck. The downside is that it takes me a long time. I am not a particularly quick knitter, and working charted lace has been an enormous challenge with a young baby to look after and just a few sacred knitting moments at the end of each day (assuming we managed to get her to sleep before our bed time).

But in this case it was well worth doing. My original ‘final’ design had a whole lot more beading than the one that made it to the published pattern. A few repeats in I realised that it was going to be too heavy to work as a shawl and would likely fall off the wearer. With a very quick bit of re-charting the problem was solved, and the sample was back underway.

The rest of the knitting progressed smoothly. Fears I had about the repeat being difficult to follow were unfounded, even with my limited attention I had no trouble picking it up and working out where I was.

Soon it was time to soak…

…and block…

…then to photograph the sample, write up the pattern and typeset…

…and edit…

Then finally it was ready to be released!

Now I can sit back and relax – but not for too long, because it’s time to start thinking about the next one!